I recently was interviewed by Nikkei Business Journal on the occasion of the publication of the Japanese translation of Reputation Rules. The following article, translated from the original Japanese that appeared in the May 7, 2012 edition of Nikkei Business Journal, summarizes the interview. It was translated by Trevor Devlin.

“What Professionals Have to Say

Four Perspectives on Re-establishing Trust

Olympus—shaken by its attempts to hide huge losses. Tokyo Electric Power—which continues to be strongly criticized following the accident at one of its nuclear power plants. There is no space here to mention all the organizations which have seen the damage go from bad to worse due to their inept responses to accidents or scandals. We asked the leading authority on ‘reputation management’ to comment on the keys to riding out the crisis when a company’s reputation is imperiled.

Daniel Diermeier – Professor at the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University

Trust in the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) has suffered severe damage since the accident at its Fukushima Daiichi (Fukushima No. 1) Nuclear Power Plant following the devastating Tohoku earthquake and tsunami of March 2011. In addition there is the case of Olympus Corporation, which saw its reputation as a top-flight enterprise suddenly turn into that of a ‘problem company’ when the dismissal of the company’s then president led to the discovery that the company books had been cooked so as to hide enormous losses. Trust in an organization can evaporate overnight as the result of a single accident or scandal, and the situation can then be further exacerbated by subsequent clumsy responses. There have been countless demonstrations of this insight in the past.

In order to safeguard against such a situation, an enterprise must actively make efforts to manage its company image among the general public, in other words engage in ‘reputation management.’

However, even if executives say that they want to manage the reputation of their company, in many cases they do not know how to go about things. With the goal of explaining to such people what risk management consists of, last year I published the book Reputation Rules (Japanese title = Hyoban wa manjimento seyo—Kigyo no fuchin o sayu suru reputeeshon senryaku, Hankyu Communications). In it I introduced the rationale behind reputation management and some specific methods for achieving it.

The first critical element in reputation management is not to leave things to some specialized internal division, declaring for example, ‘That’s a job for the Public Relations Department.’ The reason why is that when an accident or embarrassing incident occurs, no PR Department or other single unit of a company is capable on its own of stemming the loss of trust or preventing errors in response from causing a snowballing deterioration in the company’s image. That is crystal clear from the cases of TEPCO and Olympus.

It is not easy to restore a reputation once it has been shattered. The loss may be sudden, but the rehabilitation will definitely take a long time. Furthermore, the involvement of the entire company is needed to achieve this end. In order to do that, top management needs to give reputation management the same attention it gives other management capabilities, and make the necessary effort to take the initiative.

Based on that premise, we first need to consider how the reputation of an organization like a corporation is formed. And how exactly can an accident or scandal take a toll on a company’s reputation. It is necessary to thoroughly comprehend the processes at work here. My analysis will focus on the case of TEPCO, in which the accident at its Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant led to major damage to its corporate image around the world.

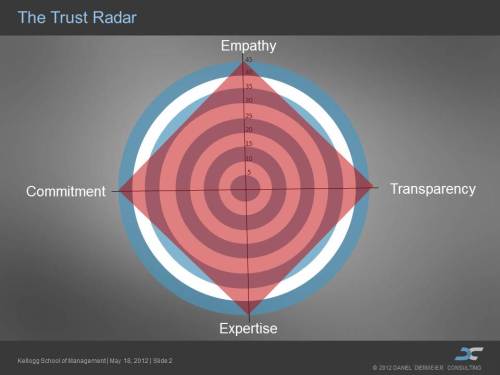

The reputation of a given company is built upon the “trust” that the company has developed among the customers who are the users of the products or services produced by that company. I believe that there are four factors which can cause the degree of trust to fluctuate up or down. These four factors are ‘transparency,’ ‘professional knowledge,’ ‘commitment’ and ’empathy.’

If these four elements are achieved in balanced fashion, the company’s reputation will be enhanced. Conversely, if these four elements are not fulfilled, the firm’s reputation will surely decline.

In addition, by measuring the degree to which it has fulfilled each of these four factors, a company can determine whether or not its corporate reputation is high. Furthermore, it can analyze which factors can be employed to increase customer trust in the company and then adopt appropriate countermeasures. The “Trust Radar” shown below explains this is schematic fashion.

Transparency, the first of these four necessary qualities, does not simply refer to the degree that information is provided to the public. It also addresses the question of how easy-to-understand is the information provided.

If the party receiving the information judges the degree of transparency to be low, it may conclude that ‘critical information is being intentionally hidden.’ For example, what is going to happen if even though critical information is revealed, it is so replete with specialist terminology that the party receiving the information cannot make heads or tails of it? There will be a strong probability that the verdict will be that the use of technical terminology is an attempt to obfuscate an issue. In such an instance, it could hardly be claimed that there is a high degree of transparency present.

In the case of TEPCO, initially the company was reluctant to release information concerning the accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. Furthermore, the information released in response to demands from the mass media was full of technical terminology, so it was hardly to be expected that the content would be comprehensible to a layman. As a result, no matter how much information TEPCO might release, the impression remained that the company ‘is hiding something.’

Second, there is the factor of ‘professional knowledge,’ which primarily refers to the degree of reliability of the technology that a company possesses. It is the members of the company themselves who know best about what they are doing, so it is only natural to expect that they would know best how to respond if any problems arise. Actually, in the majority of cases, professional knowledge does not become a factor in impairing trust in a company as it is simply assumed that the company possesses the necessary expertise.

However, in the case of TEPCO, this professional knowledge element too became a major factor in dissipating trust. Not only was there the fact that a major accident occurred at the nuclear power plant despite the presence of many experts within the company, but also the fact that TEPCO proved incapable of providing clear explanations concerning the methods being used to resolve the phenomena and problems arising from the explosions, etc. following the accident. For that reason, not only individuals who were familiar with nuclear power plants, but also citizens in general, were filled with doubts about whether TEPCO really had the professional expertise required to deal with nuclear accidents. A similar phenomenon was observable in the case of the accident in the Gulf of Mexico in which there was a major crude oil leak from a seafloor well operated by the British petroleum major BP.

The third factor is commitment, which refers to the methods and sense of responsibility displayed in responding to problems.

If a thorny problem such as a major accident or scandal occurs, people expect the CEO (chief executive officer), chairman and other leaders of the corporation to take the initiative and provide leadership, while also accepting the responsibility to explain the situation also work to resolve the issues.

In the case of TEPCO, such expectations were sadly disappointed. Not only did the top executives who were expected to provide expectations rarely appear at news conferences to offer their own explanations, in the midst of the crisis the company’s president himself was hospitalized and completely disappeared from public view. The fact that just when his company was enmeshed in a crisis the president should become unavailable was the worst possible situation imaginable.

Empathy, the fourth factor, refers to feelings of commiseration for victims. The representatives of TEPCO repeatedly voiced apologies at press conferences and in other venues, and they assiduously went about apologizing directly to those people who were forced to lead their lives as homeless evacuees as a result of the accident at Fukushima Daiichi. Nevertheless, many of the people who were being apologized to felt that these were nothing more than pro forma apologies and were not really genuinely coming from the heart. In this manner, TEPCO managed to violate all four principles required to instill trust.

Incidentally, ever since the occurrence of the previously mentioned spill from the BP oil well, that company has been working to restore the Gulf of Mexico to its original state. These efforts have been well received, and the company has enjoyed a marked recovery in degree of trust, especially in terms of the two factors of commitment and professional knowledge. As a result, the company’s reputation has been begun to rebound in the United States.

What then can be done to enhance the four elements that go into to shaping the reputation of an organization? The key here becomes organizational (corporate) governance. Next, I would like to consider the case of Olympus.

The scandal surrounding Olympus concerned efforts over several years to window-dress the company’s settlement accounts so as to conceal enormous losses. The principal victims in this case were the company’s own shareholders, and not consumers who had purchased the company’s products.

Normally, in such cases in which it is discovered that a firm’s accounts have been window-dressed, the news does not make it to the headlines of the front page of daily newspapers or become a topic for street corner conversation. Although there are exceptions, such as the case of Enron in the United States, usually such affairs do not become hot topics among average citizens. Why then should it be that the Olympus affair attracted so much attention?

What made the Olympus case special was the “story element” involved. The spotlight on the “stage” of the concealment of the losses was due to the presence of fascinating “actors” and an easy-to-understand story concerning the related “circumstances.”

The main role in this story was played by the Englishman Michael Woodford, the former president of the company. When after he had gained the position as leader of this world-renowned brand name company the Board of Directors suddenly decided to oust him, Woodford refused to go softly into the night and instead reacted by disclosing the company’s internal secrets. The development of events in the case was truly dramatic. They garnered attention from overseas, so that the situation developed into a major scandal which ended up attracting the global media as well as investigative authorities.

In order to resurrect the image of Olympus, which had thus been pulled down into the dust both at home and abroad, at the very least there needs to greatly improve governance by the Board of Directors.

After all, with the very existence of the company in peril, the Board of Directors has no choice but to commit itself to resolutely carrying out reforms. In order to respond to the situation, the Board might have to dismiss its current leadership, or otherwise move to rapidly implement reforms. In a case where the Board of Directors is under the control of top executives, so that it cannot voluntarily make appropriate decisions, it is impossible for it to get a handle on conditions or rectify conditions, meaning that things will deteriorate even further.

In the case of Olympus, if governance by the Board of Directors had been functioning properly, at an early stage there would have been a wholesale shakeup among the directors as well as within the ranks of top management, so that the running of the company would have been entrusted to individuals who could improve the company’s soiled image, or take other such measures. In that case, it might have been possible to extinguish the “fire” at an early stage.

The fact is that when a company has lost the confidence of its customers and investors, there are instances in which it can prove effective to bring in a highly respected third party.

For example, at the beginning of the 1990s in the United States the major investment firm Salomon Brothers (the current Salomon Smith Barney) was plagued by numerous scandals, including improper bids for U.S. Treasuries. Shortly after discovery of the incidents, an executive within the company was appointed president.

This president revamped the management team, inviting in renowned investor Warren Buffett. The market’s immense trust in Buffett proved highly effective in restoring trust in the company.

Such countermeasures for dealing with the situation after problems have caused a company’s reputation to be hard hit require restructuring in terms of corporate governance. Before fashioning and implementing such countermeasures, it is critical to evaluate the impact caused by the problems in question. If managers error in judging the degree of impact, then naturally the countermeasures they adopt to deal with the situation will likely not fare well.

Here I would like to introduce come effective concepts for evaluating the impacts caused by incidents and scandals.

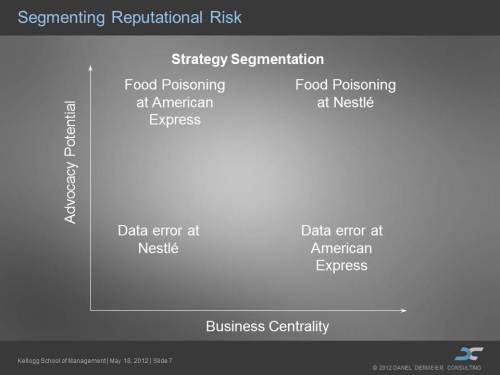

Please take a look at the graph on the following page. The vertical axis represents the degree of shock damage delivered to the corporate reputation by an incident, scandal or other problem, while the horizontal axis indicates the degree of importance the issue has on the business of the company (core business or not). The background considered when creating this graph is that when a given issue arises the reality is that the impact on a company’s reputation will vary according to company and type of industry.

For example, in the summer of 2009 the problem of rapid acceleration of Toyota vehicles surfaced in the United States. For all automakers, the issue of the safety of the motor vehicles which are their mainstay products looms very large. But for Toyota the importance of safety surpasses that at other carmakers. That is because the value of the Toyota brand is rooted in its superior product quality vis-a-vis other brands.

I think I can say without fear of being judged wrong that if, for example, the luxury British carmaker Jaguar suffered a similar problem with rapid acceleration, it would not have caused the same amount of reputational damage as what happened to Toyota. That is because for Jaguar owners another concern, namely design, trumps vehicle safety.

Or let’s consider another case. Assume that a case of food poisoning occurred in the United States at the cafeteria of a motor vehicle manufacturer like Toyota. However, since food poisoning has nothing to do with the core operations of the carmaker, food safety or quality would have nothing to do with the core competitiveness of Toyota.

Nevertheless, what would be the reaction if a similar case of food poisoning occurred in the employee cafeteria of the hamburger chain McDonald’s or another major restaurant chain? Even though the actual fact of there being victims of food poisoning would be the same for both companies, the question of safety in the employee cafeteria would have no direct relationship to the core business activities of an automaker, while it would have a direct relationship to the core business of a restaurant firm. Thus, the impact exerted by an incident on such a corporation’s reputation would be incomparably greater than in the case of the automaker.

In other words, the degree to which a given problem is related to the business activities of an enterprise and the degree of such impact are extremely important considerations. This is the key in determining the scale of the blow that will be delivered to its reputation.

In measuring the degree of the blow to the reputation, another important concept is the “degree of attention paid.” Specifically, I would say that a judgment needs to be made whether “this issue will become news reported on the front page of major newspapers in Japan and overseas.”

Well then, what kinds of incidents and accidents are likely to become the lead story on page one of newspapers. Two factors are determinative.

First: ‘How important would this issue be considered within the country in question?’ Although a certain issue might garner a tremendous amount of attention within a country, it would not attract nearly as much notice in another country. For example, when it comes to animal welfare, this is very important concern in Great Britain, although that is not true in France. When considering the impact of an issue, it is essential for top managers to understand the cultural background of the country or region involved.

Let me offer another specific example. When it was discovered in 2005 that the now defunct Kanebo Ltd. had embellished its financial results, it became a big story in Japan and a Japanese auditing firm was forced to undergo a major restructuring as a result. However, there was hardly any real-time reporting of the affair in the United States, and in the United Kingdom it was largely limited to a bit of reporting in the Financial Times. Kanebo was not a very well known corporate name in Europe or North America. If it had involved a scandal for a company with a international name value on the order of Toyota, no doubt it would have become global news.

In judging the degree of notoriety another important factor is, as mentioned earlier, the degree to which a story line is present or absent. There is always trouble like the Toyoda sudden acceleration issue popping up. However, what caused the problem to grow so big was the fact that it made a good story.

The initial impetus for the story was an accident in the State of California in which four passengers riding in a Toyota died. The fact that one of the passengers in the vehicle sought to get help by cellphone was given wide coverage in the U.S. media. That triggered strong interest in the U.S. public, and it subsequently developed into a major issue involving a large-scale recall (recall and no-cost correction of the problem).

What top management needs to do in such a situation is to try to understand how their strategic situation has changed. If that had been done, then in the case of the aforementioned accident which occurred in California, it would not have been considered nothing more than an accident on par with about 500 such accidents which occur annually. However, by the time that the story of the accident had become widely circulated, it no longer was merely one incident among a kind of accident that frequently occurs.

What things like this force us to recognize is that managers need to have the skill to quickly judge that ‘this story has spread, and the problem has shifted to another dimension into the realm of crisis.’ No matter what the issue might be, if a good story line is involved, it is going to attract attention. When that happens, if you try to offer a defense from a technical perspective, then you can be pretty well sure that most people will not be willing to lend an ear to difficult-to-understand explanations. (In fact, it was later proven that the cause of the accident in question was not related to the electronic system in Toyota vehicles, but that vindication took more than a year.)

In order to gain attention, it is common for corporations to try to use the appeal of celebrities, athletes or other well-known public figures to do all they can to attract consumers to that company’s products and services. However, in cases where a good story line causes a lot of attention to be focused on an accident or scandal, the improper behavior of the people involved can make the situation even worse.

I am convinced that people basically want to trust companies. They also expect companies to develop the four components of trust, namely ‘transparency,’ ‘professional knowledge,’ ‘commitment’ and ’empathy’ to a high degree. When unexpected problems arise, people are overcome with anger and fear, and they feel that these expectations have been betrayed.

Even if a corporation believes that the reactions among people are unwarranted, all they can do is soldier on and strive relentlessly to recover their trust. In the final analysis, the hearts of consumers are not things that you can expect to control completely.”