Welcome to our second annual list of the top ten crises of the year. This was another banner year for corporate crises and scandals.

1. Global Banking

2012 was a particularly harsh year for global banking. Bank of America, Deutsche Bank, Goldman Sachs, HSBC, J.P. Morgan Chase, Morgan Stanley, Standard Charter, and UBS all would have been strong candidates to make the 2012 list on their own. Issues included the Libor scandal, rogue traders, fraud, money laundering, and a botched IPO (Facebook), among others. In addition, prominent hedge fund managers were convicted (Galleon) or investigated (SAC Capital) over insider trading, as U.S. authorities significantly stepped up their investigative and enforcement efforts.

All this contributed to a new low in public trust for an industry already held in low public esteem. But how much does this matter? Cynics may argue that while the entire industry is mistrusted, it still fulfills an irreplaceable function in global commerce. Moreover, the size and interconnectedness of global banks may make them (in the words of Andrew Bailey, chief executive designate of the UK’s Prudential Regulation Authority) “too big to prosecute.” Finally, if the entire industry is mistrusted, no one bank can be singled out. But this view is short-sighted; it overlooks the increasing willingness by politicians and regulators to take action. Public officials may act due to genuine outrage or policy concern, or in response to public pressure. The result is that financial institutions increasingly need to play defense; they fight merely to continue existing business practices – not an encouraging prospect.

2. Costa Concordia

According to Karl Marx (a quote recently revived in the movie Argo) history repeats as tragedy and ends as farce. But as the Costa Concordia crisis showed, sometimes the move from tragedy to farce requires no repetition. As a reminder, the cruise ship Costa Concordia, operated by Costa Crociere S.p.A. and owned by Carnival Corp., partially sank on the night of Jan. 13, 2012, after hitting a reef off of the Italian coast and running aground at Isola del Giglio. More than 4,000 people on board had to be evacuated (more than thirty were confirmed dead), and the images of the half-sunken cruise liner made evening news across the world (it still warranted a 60 Minutes story as late as last weekend). Things took a turn to the bizarre when it became known that Captain Francesco Schettino had deviated from the ship’s computer-programmed route to treat people on Isola del Giglio to the spectacle of a close sail-past or “near-shore salute.” Captain Schettino was later charged (among other things) with abandoning incapacitated passengers. To refute the allegations, Captain Schettino had claimed that he had fallen into a lifeboat by accident. In addition to these operatic details, the crisis raised serious issues over safety practices at the ship’s operating company, a forceful reminder that, once a company finds itself in the spotlight, all its previous actions will be scrutinized as well.

3. Apple and Foxconn

A soaring stock price, passionate customers, and an iconic status are no guarantees against reputational crises. This is one of the lessons from the controversy over labor conditions at Apple supplier Foxconn. Following months of controversy over illegal overtime, inadequate safety conditions and poor workers’ housing, and highlighted by a string of reported suicides by distraught workers, Apple and its main manufacturing contractor, Foxconn, agreed to significantly improve labor conditions at Chinese factories. Foxconn’s decision to make improvements followed an investigation by the Fair Labor Association (FLA) which found multiple violations of labor law, including extreme hours and unpaid overtime. Apple’s initial response was slow and somewhat evasive, but eventually Apple’s new CEO Tim Cook decided to take a leadership position on the issue of global labor standards.

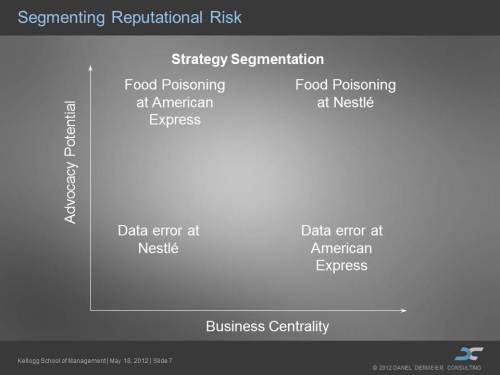

This case illustrates an increasingly important phenomenon: the rise of private regulation of global commerce via reputational crises. The strategy works as follows: advocacy groups target a particularly well-known company that is likely to generate broad media coverage. If successful, the reputational damage forces the company to change its business practices, setting a benchmark for the industry. This “regulatory” activity is entirely driven by private entities, while public entities play little to no role. Even though Foxconn’s compliance with new standards is not mandated by a new law, the practical effect is the same. This is the force of regulation through reputation.

4. Walmart

It was an annus horribilis for Walmart. What started as an isolated corruption case in Mexico has now engulfed the company as a whole involving senior management and the board. A December 18 article in the New York Times states this as follows: “Rather Walmart de Mexico was an aggressive and creative corrupter offering large payoffs to get what the law otherwise prohibited. ” Moreover, according to the same article, Walmart’s leadership was informed about the allegations, but decided to shut them down. This (still ongoing) issue follows on the heels of the recent fire at the Tazreen Fashions factory in Bangladesh, a maker of clothing items for Walmart and other retailers. Bangladesh is the world’s second largest apparel manufacturer after China, and the fire, caused by gross negligence, has refocused attention on the country’s unsafe working conditions.

These crises have re-energized the anti-Walmart coalition in the U.S., which had lost some of its steam after Walmart embraced sustainable supply chain practices, universal health care, and even moderated its anti-union stance, at least in some instances. The case also points to the exposure for globally operating companies due to supply-chain risk: reputational risk cannot be outsourced.

5. Lance Armstrong and Livestrong

When Lance Armstrong was stripped of his record seven Tour de France titles following the damning report by the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency (USADA), and lost major sponsors Nike and Anheuser-Busch, the crisis quickly spilled over to his cancer foundation Livestrong. Although Armstrong stepped down as chairman, the foundation has faced the difficult challenge of creating a successful separate existence after being so closely associated with its founder.

This is not the first case where a personal scandal has created severe difficulties for associated entities. Examples include Martha Stewart’s Omnimedia, as well as Tiger Woods’ corporate sponsors. The risk associated with highly personal brands is that the personal life of the endorser/founder/owner is closely tied to the success of the business entity. In case of a personal scandal, the positive spillover from an admired celebrity can quickly turn to a reputational crisis for the associated entity, now caused by a negative spillover, especially if the scandal undermines the very values on which the personal brand was built. Things seem to go reasonably well, so far. Livestrong’s donations actually increased immediately after Armstrong’s resignation, though some donors asked for their money back.

6. Susan G. Komen Foundation

Nonprofits feature prominently this year on this year’s list. This may be a coincidence, or a reflection of a broader trend that managing reputational risk is as important for nonprofits as for companies. After all, what are the assets of successful non-profits other than their people and their reputation?

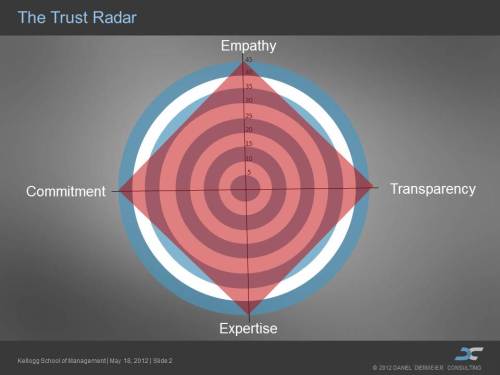

Nonprofits may believe that they have a reservoir of goodwill, a trust bank account that can be drawn upon when times get tough. This view is largely misguided. Trust does not work like a bank account; it resembles a currency. The same message coming from a trusted source will have more credibility. But if trust is not maintained, this multiplier effect can vanish quickly. When Susan G. Komen for the Cure, the nation’s largest breast cancer advocacy organization, considered cutting off most of its financial support to Planned Parenthood in late January 2012, it was quickly engulfed in a firestorm of protest, initially stirred by social media advocacy before it reached traditional media channels. Now caught on the battle lines between pro-life and pro-choice advocacy groups, the leadership quickly stumbled. Unconvincing, overly bureaucratic, justifications gave way to a quick reversal of its decision to cut funding for Planned Parenthood. Subsequently, CEO Nancy Brinker and President Elizabeth Thompson announced plans to step down from their posts. But recovery has been difficult. Participation at its signature Race for the Cure is down by 19 percent, according to a recent New York Times article. Once the Komen foundation had been associated with the vitriolic abortion debate, any decision was criticized by somebody, a common feature of highly polarized issues. During last October’s National Breast Cancer Awareness month, the foundation ran a new ad campaign focusing on the individual women whose lives have been saved by the foundation’s work. While this particular attempt to refocus public attention on the mission was well-executed, it remains to be seen whether the Komen foundation can ever fully recover its past status.

7. Chick-fil-A

Another controversial issue, another company. This time the controversy was over gay rights and the company was the family-owned fast food chain Chick-fil-A. The uproar began in late July when President and COO Dan T. Cathy stated that Chick-fil-A supported “the biblical definition of the family unit.” While the deeply religious roots of Chick-fil-A’s founder and family owners were well known, the new comments quickly led to boycott threats by gay rights groups, statements by public officials in cities such as Boston or Chicago that the company was not welcome there, and the decision by the Jim Henson Company, creator of the Muppets, to no longer supply the company with toys.

What made this case particularly interesting was the support of Chick-fil-A by conservative advocacy groups and politicians, including then candidate for the Republican presidential nomination Rick Santorum and former presidential candidate Mike Huckabee. Conservatives asked supporters to increase their visits, effectively organizing a “buy-cott.” The sales impact on Chick-fil-A seems to have been limited, raising the intriguing and somewhat worrisome specter of consumer preferences being significantly correlated with political ideologies. Picture the Whole Foods shopper compared to the Cracker Barrel customer, Starbucks versus Dunkin Donuts. But before embracing another new marketing fad companies should be careful with (unintentionally?) defining themselves as a “Republican” or “Democractic” brand. Otherwise, they will be in for some interesting times.

For more details on the impact of boycotts, see my Harvard Business Review blog post.

8. The BBC

This fall the BBC faced the biggest crisis since its existence. The first blow was revelations that TV personality Jimmy Savile had sexually abused children while he worked for the BBC. Moreover, prior to the revelations by a rival news program, an investigation conducted by a BBC’s news program had uncovered credible evidence that Savile was a pedophile. Yet the BBC canceled the investigation in December 2011, the same month the network ran a glowing tribute to Savile. A recent report on the incident pointed to chaos and confusion rather than a cover-up.

But that was not all. In the aftermath of the Jimmy Savile scandal, BBC flagship program Newsnight investigated a North Wales child abuse scandal. A former resident of the Bryn Estyn children’s home was reported on Newsnight claiming that a prominent but unnamed former Conservative politician had sexually abused him during the 1970s. Rumors on Twitter and other social media named the politician. After The Guardian reported a possible case of mistaken identity, the politician stated that the allegations were wholly false and seriously defamatory. The accuser unreservedly apologized, stating that as soon as he saw a photograph of the individual, he realized that he had been mistaken. The BBC subsequently apologized.

The decision to broadcast the Newsnight report without contacting the person first lead to further criticism of the BBC, and the resignation of its Director-General George Entwistle. Following Entwistle’s resignation, Lord Patten, Chairman of the BBC Trust, called for a “thorough, radical, structural overhaul” of the organization. Tony Hall, a former BBC journalist and subsequent successful director of the Royal Opera House, was appointed the head of the BBC. While this appointment inspired confidence, the BBC has a tough road ahead.

9. Japanese companies in China

We can now add “country of origin” to the ever increasing list of headaches for today’s multinational companies. The most recent example is Japanese companies operating in China following the controversy over a cluster of uninhabited islands northeast of Taiwan. This conflict has had severe consequences for Japanese companies doing business in China. Compared to last year, Toyota has seen its sales drop by 49 percent, Honda by 40 percent, and Nissan by 35 percent.

Other examples of this phenomenon include the 2005 boycotts of Danish products in the Muslin world after the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten published satirical cartoons which depicted the prophet Mohammed, as well as the oil company CITGO, which is owned by Venezuela’s state-owned national oil company. Venezuela’s leader Hugo Chávez gave a highly inflammatory speech in 2006 where he called then President George W. Bush the “devil” and “sick man.” As a result, CITGO faced immediate calls for boycotts in the U.S.

These intense reactions are usually triggered by moral outrage, either because of violated national pride or firmly held religious beliefs. In the ensuing angry protests, companies may find themselves the target of popular rage. The strategic options for companies to respond are limited. They usually are well-advised to stay out of the political debate, in part because allying themselves with one government will alienate the other. A more promising strategy is to highlight local roots. The problem with such strategies is that they run counter to a brand-based strategy that has downplayed local independence up to this point. Having it both ways is difficult for companies: you live by the brand, you die by the brand. This insight holds even if the brand damage is beyond the company’s control.

10. The NFL

The NFL is by far the most successful sports league in the United States. TV viewership is up and fan passion runs as high as ever. Moreover, compared to other leagues (the NHL comes to mind) bargaining issues were resolved successfully leading to a landmark 10 year agreement. So, why did the NFL make the list? No, it’s not the issue of replacement referees, highlighted by the missed call in the Packers-Seahawks game. The issue is player safety, especially the issue of head trauma and concussions that are being linked to dementia and player suicides. In June 2012, more than 2,000 former NFL players filed a lawsuit against the NFL, the biggest sports-related lawsuit ever, accusing the league of concealing information linking football-related injuries to long-term brain damage. The suit alleges that the “NFL exacerbated the health risk by promoting the game’s violence” and “deliberately and fraudulently” mislead players about the link between concussions and long-term brain injuries.

What we have here is an example of slow-burning crisis that remains unresolved and leads to repeated flare-ups, especially whenever another player tragedy hits the headlines. The NFL has responded decisively, donating $30 million to the National Institutes of Health for brain-related research, changing concussion policies, and engaging in ongoing rule changes. That said, at this point there is no solution to the problem. Moreover, some of the policies intended to better protect players are resented by some players, e.g. the controversy over penalties for Steelers linebacker James Harrison. The recent decision by former commissioner Paul Tagliabue to vacate player suspensions over the Saints bounty scandal was a further setback in this direction. Maintaining the popularity of the game while making it safer will be a challenge for years to come.